In the wake of the 3.11 tragedy: to go or not to go?

AI TranslationYesterday was a bad and stressful day. Highway, trucks, cold. I've been riding 70-80 kilometers day after day, so my knees are starting to hurt. This has stopped being a journey and become some kind of mechanical pedaling with half-closed eyes. At first I wanted to sleep at a covered bus stop, but mosquitoes started flying around and biting my hands. In the morning steam began rising from the damp soil and grass up into the cloudless sky — as if clouds had spent the night on the ground. Half an hour later the sky was shrouded in gray mass. I found shelter at a Shinto temple when it was already light. Spreading out my camping mat, I passed out.

Sometimes you want to remember a moment exactly as you see it when you open your eyes. That's how I want to remember this morning. The sun was shining brightly, and the sky was clear and blue again. This is a completely new day, both weather-wise and feeling-wise. Around me are just fields, streams and wooden houses. Where can you get coffee in these parts? After five hundred meters I ran into a sign with a picture of coffee, a plate and a heart. A guy with glasses beckoned me with his hand. — You want coffee? Come on over here, free! — this is exactly how every morning should start. The place is called Aimaki after the owner's surname and is located in the Kesennuma area, Iwate prefecture.

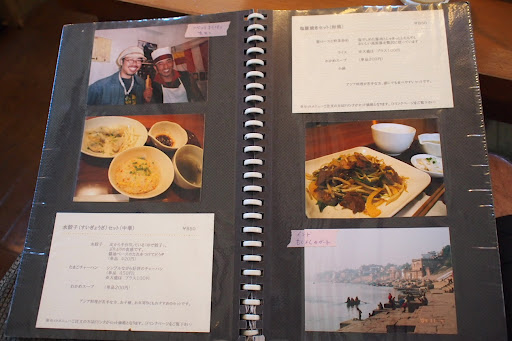

— I love traveling myself, my wife and I have been all over Asia. — He handed me a menu that contained dishes from the places they'd visited. Like a culinary family album. At the bar counter — a shelf with magazines, photographs. I noticed a radiation measuring device. Among the magazines — a memorial album with photos of the tragedy. On the very first page — a huge wave, then destruction, a tent city, food distribution and, finally, photos of children born on that day. Another memorial album with photos of these places before the tsunami.

He served me a cold cappuccino. — Where are you heading next? — I don't know. Maybe through Fukushima, I still haven't figured out if it's dangerous there or not. — Listen to me, it's dangerous there. Don't believe what they say. The government says there's no radiation to get people back to their normal lives, but it's dangerous there. — How do you know? — I've talked to people, there people often go to doctors complaining of excessive fatigue, nausea. Products from there are dangerous, don't buy them, I don't buy products from Fukushima for my restaurant.

A few days ago, with the help of my Japanese friends, I contacted the Japanese tourism ministry. Knowing about my intentions to ride through Fukushima, they asked me to clarify how they could help me. Three days have passed, but there's still no answer.

I rode to Sendai all day, 107 kilometers, arriving deep in thought. To go or not to go? I couldn't find a CS host. At eleven in the evening, I crashed on the floor of a hostel room after a can of beer and slept until ten in the morning. At noon I had already bought a train ticket to Tokyo and called Richard. — Oh! Hi, how are you doing? How's your trip? — Everything's great, how are you? — I'm at work right now. — Can I come over tonight? — Yeah, no problem. I have a lot of people at my house right now: two other cyclists are staying over, but we'll find you a place, don't worry. In Sendai on September 8-9 there's a street jazz festival. Blending in with the crowd to the sounds of live music — that's what I need.

At nine in the evening I'm already in Tokyo, a distance of five days by bicycle was covered in an hour and a half. Before that in Sendai, at a gas station, I washed my bike, remembering that it's white. Now everyone's staring at it. At Shinagawa station in Tokyo, six drunk insurance company workers approached me, they had been at a restaurant with their whole team. — Good for you for deciding on this journey. — Thanks. The drunkest of them looked like Tom Hanks, Asian version. — But tell me... why Japan? — he struggled to pronounce, slightly closing his eyes. — It's beautiful here. — I said this the way I used to say it on Hokkaido, then on Honshu at the beginning, but images from the last few days flashed through my head. He extended his hand to me, placing his other one on my shoulder. — You're awesome... I respect you... Then he said something in Japanese to his colleagues, and a minute later 6000 yen was stuffed into my pocket.

Recovering my strength before the ride.