Japanese god or religion in Japan

AI TranslationWhere did this temple come from? Many who have traveled through Japan have observed temples in unpredictable places — from residential neighborhoods to industrial centers, at markets, in forests, on mountains. On Mayajima island there's a temple whose red gates stand in water — you can't see anything like that anywhere else in the world.

Buddhists or Shinto It's hard to say which religion is the main one in Japan. Statistics say Shinto, then Buddhism, and then Christianity trailing far behind. Those who've looked into this question have probably already remembered the famous phrase that a Japanese person is born Shinto and dies Buddhist. I won't beat this already overused story to death. From my own observations, I'll conclude that young Japanese people are neither one nor the other. Most consider themselves Buddhists, but it's more a nod to tradition, an inseparable part of their environment (like a Lenin monument in every city), part of everyday life rather than faith. Coming to a temple, tossing a couple coins into a wooden box and, clapping your hands, saying some phrase — it's cool from time to time.

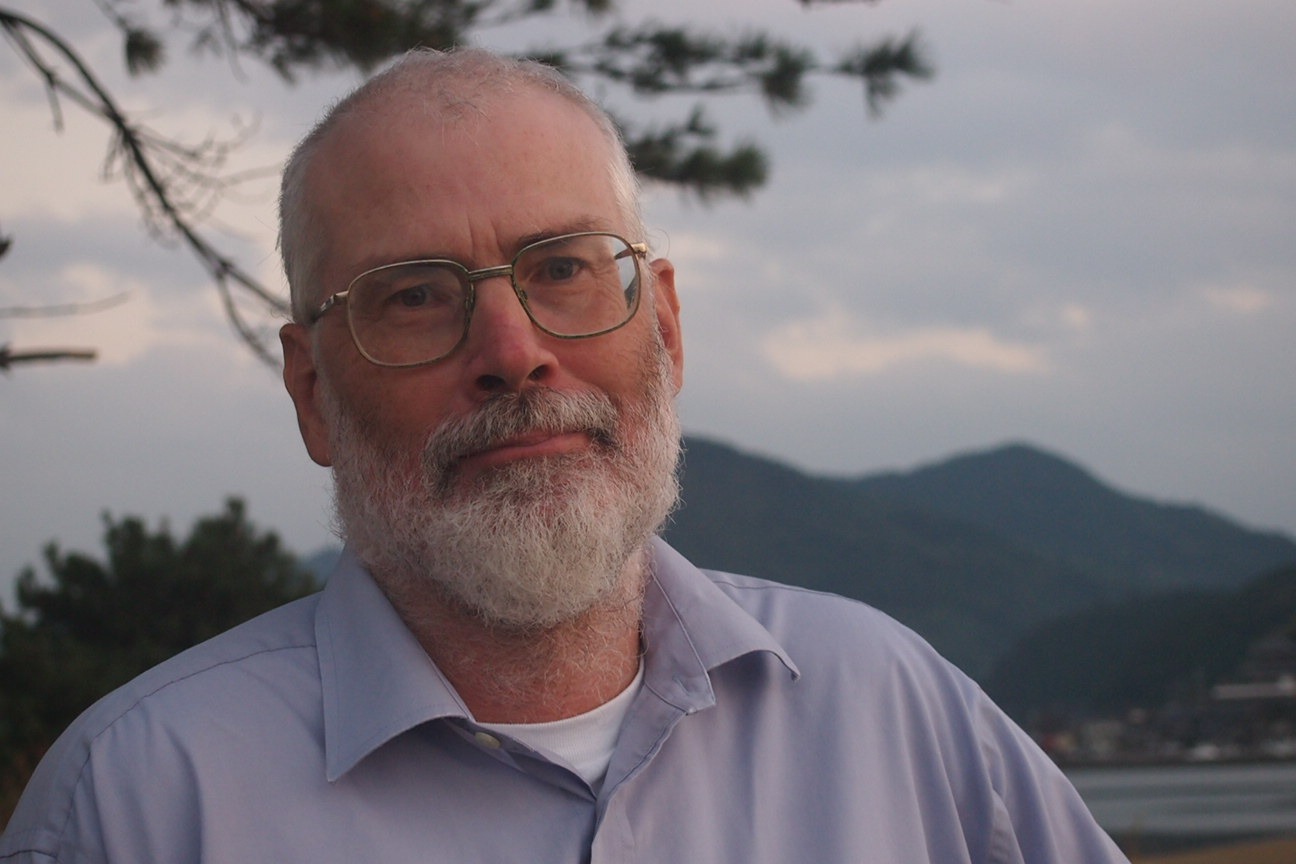

Christian sprinkles In the city of Hagi, in southern Honshu, I met an elderly Brit, a Catholic priest who makes his living conducting Christian-style weddings. And again, it's not about faith — the Christian flavor of wedding ceremonies is just exotic for Japanese people and is popular. The pastor himself doesn't see anything offensive in this:

"But I'm still joining them in marriage before the face of God" — like, they might not be aware, but I'm doing my job.

The question of Japanese Christianity is interesting for another reason too. Imagine isolated 16th-century Japan. A country that only knows about India and China among all other countries on earth, has its own culture and established values. A man with unusually shaped eyes steps onto this land, strangely dressed, doesn't know a word of Japanese. The question: how did the first missionary manage to convince the first Japanese person, at that time a Buddhist or Shintoist, that a thousand and a half years ago somewhere in the Middle East (what's that?) there lived a man named Jesus Christ, he died for his sins and is generally his god. How? The task seems even more impossible when I fail in my attempts to find out from a Japanese person where the grocery store is.

The pastor's answer to my question started flawlessly: "God helped them in their holy intention..." — the rest doesn't matter. Still, you can get some idea about this. In Eiji Yoshikawa's book "The Honor of the Samurai," there's a moment where two Catholic priests, hurrying to an audience with Prince Nobunaga in Kyoto, rushed to save a drowning boy from a river, thereby winning favor from the boy's parents and the peasants watching the scene. One from the crowd threw out the phrase "Maybe their god really is as great as they say." And so the first pilgrims conquered the poor with good deeds, while the upper classes were surrounded by Buddhist priests. But Prince Nobunaga was neutral toward Western culture. "We need to chew it up and spit it out," he said. He was also the first to allow building a church in Japan, advancing his political interests. Another category open to Christianity were "progressive" Japanese studying Western sciences.

The pastor also told me about the modern way of converting Japanese people to Christianity. According to him, his approach differs from the conventional one. The pastor made a sign one meter high and twenty wide, with Japanese text saying "Faith in God is your only chance for salvation." Describing his idea, the pastor's eyes lit up as if he were sharing a brilliant slogan with me. With this sign, he visits large open-air events and stands there, waiting for people to approach him. Relaxed, slightly drunk young people easily make contact, the pastor shares God's words with them, but he has no way to track the further spiritual growth of the newly enlightened.